Mauricio Braucci is the Italian scriptwriter who wrote the acclaimed film Gomorrah. Together with the US director Abel Ferrara he made a film about Pier Paolo Pasolini, one of the greatest filmmakers of the 20th century. The 40th anniversary of his murder will be marked next year.

Pier Paolo Pasolini was a versatile person: he was a filmmaker, writer, intellectual. What did you focus on while making the film about him?

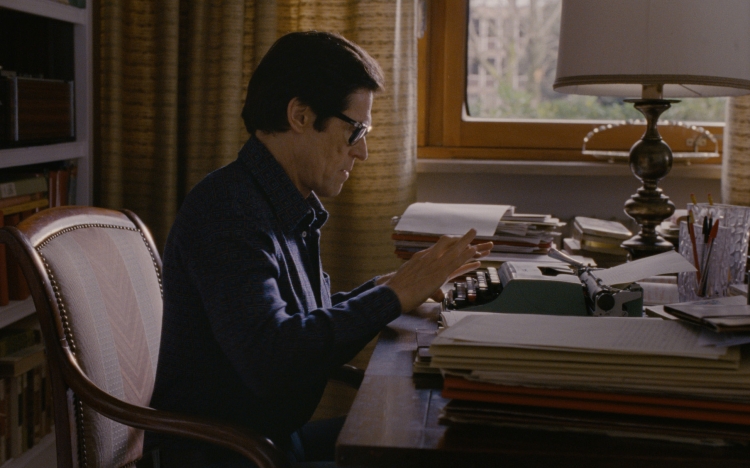

We carried out a very comprehensive research, from written sources to interviews, in order to recreate his last days and eliminate the hypotheses about his death as much as possible. We recorded hours and hours of interviews with his parents, friends and experts studying his work. The film is focused on the last two days of Pasolini's life, his film Salò, polemics about Lutheran Letters and his unfinished works: novel Petrolio and film Porno-Teo-Kolossal, in which lucidity and despair were supposed to manifest themselves more than ever before. These works reflect a Pasolini who wanted to criticize the social status quo with blasphemy once again and who died trying to do it.

Did you go for a classic narrative in your film or for some more challenging solutions?

While our basic idea was to depict Pasolini's last days primarily by focusing on the facts, we also wanted to familiarize the viewers with what he pondered on in that last phase – in terms of art and politics. This is why we went for a specific structure with ellipses and a three-level narrative: one comprises Pasolini's everyday life, the other his exciting nightlife and the third one his stream of thoughts and mental images that, I believe, marked his last days. I think the film can be compared with a painting – you have this interplay of layers of colors of different shades, transparent enough to enable you to make out each and every one of them. In my opinion, that makes the result more intense and clear.

What was it like to work with director Abel Ferrara?

Abel got the idea to make such a film years ago, ever since he first saw Pasolini's films in New York. Given their poetics, I understand this obsession of his. We shared a house in Rome for five months, "meditating" over the project, almost like in a monastery. We were writing it and shooting it at the same time. I was always on the set, modifying the script as we went along, often working with the actors, too. I greatly admire Abel for not hesitating to experiment. The audience's expectations do not bother him too much; he likes taking risks and using innovative approaches.

Critics and audiences agree that Willem Dafoe was an excellent choice for the title role. What was it like to work with him?

First of all, we intensively went through the dialogue with him because he wanted to understand it well and master Italian language, not just utter it. I don't think he was an excellent choice – I think he was the best choice. He created his version of Pasolini instead of becoming his imitation – which often happens in biopics. Such an approach didn't make it any easier for him. The Pasolini thus created is the result of Ferrara's directorial approach: everybody on the set, including the scriptwriter and make-up artist, gets a chance to co-create his character.

Since Pasolini was a merciless critic of the society of those days, is the film a depiction of the Italy of the 1970s or of the present-day?

In the last two interviews he gave, Pasolini spoke a lot about these subjects. This is why our film primarily presents him as a historical character – and as a prophet whose criticism of the process of dehumanization of society from 1970s on has turned out to be true, both in reality and on silver screen.